A glimpse into high-performance sailing

Summary of NGCM chat session held on Wednesday 17 June 2020; this included a presentation by Marin Lauber “Faster than the wind; a glimpse into high-performance sailing” followed by some questions and a chance to catch up with fellow NGCM students and academics.

The field of high-performance sailing yachts has seen some drastic changes in the last decade. The majority of those changes are related to the ability of sailing yachts to reduce the hydrodynamic drag. Thanks to the help of hydrofoils. While the idea of removing part of the resistance by lifting the hull out of the water is not new, the first foiling motor yacht was sailed in 1906 on Lake Maggiore by Enrico Forlanini and reached the impressive speed of 36.9 knots[1].

[1] 1 knots = 1.852 km/h = 0.5144 m/s

Hydrofoils allow reducing the viscous and wave resistance drastically, thus allowing greater speeds with the same power. The first use of hydrofoils on sailing yacht followed soon after that. In 1955, by a chap of the name of Gordon Baker that was backed by the US Navy.

Since then, numbers of variations of the hydrofoil concept have been used to improve the top speed of those yachts. Some of these iconic yachts include Icarus, (1979, 20.70 knots), the Trifoiler (1992, 43.55 knots), Technique Avancées (1997, 41.12 knots) and L’Hydroptère (2009, 51.36 knots). Off course, some of those attempts resulted in some catastrophic failures, for example, the capsize of L’Hydroptère, putting an abrupt end to the project.

Until 2013, most of these attempts have been at breaking the top speed record, and barely any racing yachts used hydrofoils. The 2013 America’s Cup provided the missing link between the two. The Kiwi team realized that a loop-hole in the rule allowed yachts to use hydrofoils. They developed a foiling boat “in secret” that showed some awe-inspiring performances (47.57 knots in 21.8 knots of wind, almost 2.5 times the speed of the wind). Unfortunately, the Americans saw the gain that could achievable with the use of hydrofoils and adapted their design and were able to keep the Cup. Since then, foiling yacht have been racing each other on a more regular basis, and they have become much more accessible to “every day” sailors.

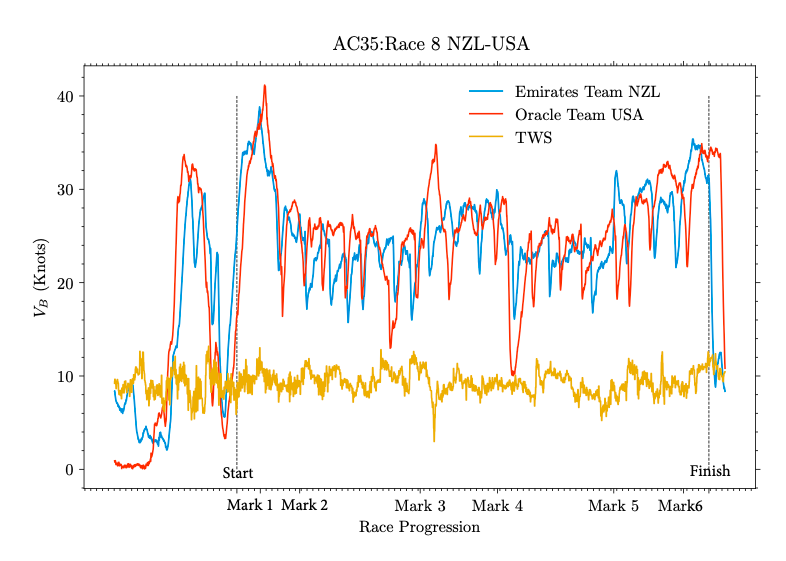

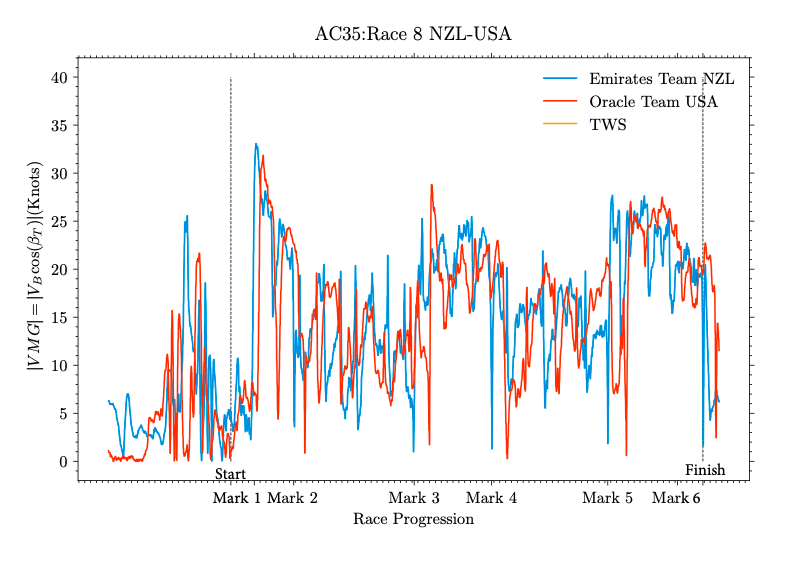

Perhaps an even more significant leap forward occurred during the 2017 America’s Cup (there is a reason why we sometimes refer to it as the pinnacle of sailing). This time, the design brief allowed for fully foiling catamarans and Team were pushing to achieve a dry lap, a lap around the racecourse without the hulls touching the water. With huge design team behind them, they eventually achieved this goal, with Emirates Team New Zealand being the first to complete a dry lap, during race 8 of the Final Americas Cup match against Oracle Team USA. With awe-inspiring performances from both participants. With only 9.26 knots of wind on average (leaves are moving vigorously), they were able to achieve top speeds above 40 knots, almost 4.5 times the speed of the wind! Quite an achievement. While Oracle Team USA reached the best top speed reached, they were unable to win the race against the Kiwi boat. In sailing, speed is not the only most important quality for a yacht; the ability to go upwind is another. Combination of both is what’s called the Velocity Made Good (VMG), which is the component of your velocity vector that is making you go upwind

Looking at the VMG’s of boat contenders, there is clear advantage for the Kiwi boat (right figure).

The next cycle of America’s Cup that will happen in 2021 (hopefully), using another foiling yacht design, still aims at these dry laps. From catamaran, we are now back to monohulls (75 feet), and one could spot the British entry training on the Solent!

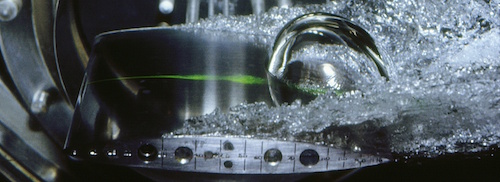

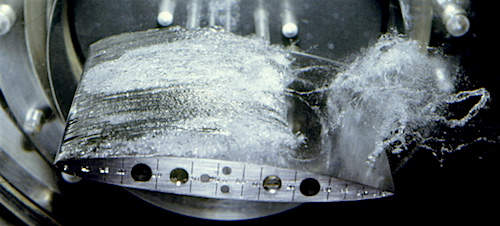

With all those improvements in such a small amount of time, there remains one question; where is the limit? In fact, we have already reached it. At those speeds, the low pressure generated on the extrados of the hydrofoil plunges below the vapour pressure of water, making the water boil at ambient temperature. This is cavitation, and it is almost inevitable above 45 knots. This phenomenon is usually observed on propeller blades and can cause severe damages, in addition to significantly increasing the resistance.

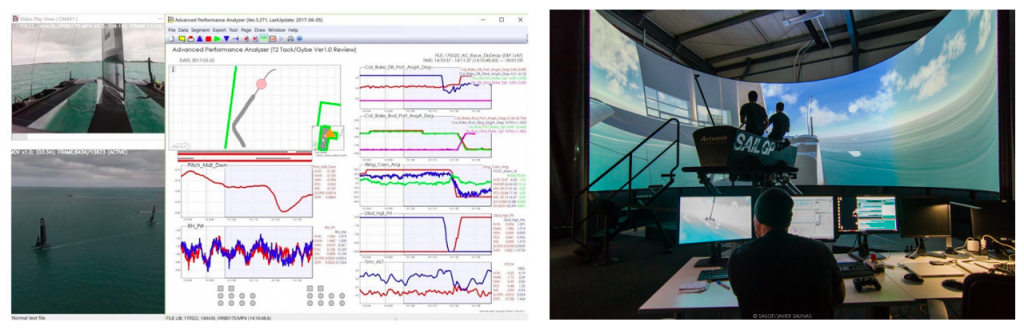

Perhaps part of the high-performance sailing yacht that is more related to the NGCM is the type of modelling that takes place in the design team of those marvellous racing machines. Apart from the obvious computational fluid and solid mechanics, there are some exciting modelling going on. Using complex Velocity Prediction Programs (VPP’s) designer can estimate the yachts’ performance. These are based on a three-degrees of freedom equilibrium, but much more complex models are also available (6 DOF, and dynamic). These are effectively used similarly to Formula 1 Team who used their model to predict lap times. These high-fidelity models can be used as the physical model behind yacht simulators, allowing the sailors to sail the boat without having to build it first. Also, data gathering and analysis is now the norm for those high budget teams.

To conclude, there has been some exciting progress in the design of high-performance sailing yachts, first with the addition of hydrofoils, allowing the speed of the yacht to be drastically improved. Then computational method has been an excellent tool to develop this technology further, and push some sailing teams at the forefront of technology.

By Marin Lauber

PDF presentation can be found here.